Reading Southern agricultural periodicals, one is more likely to see advice on protecting crops from birds than protecting birds themselves. Take, for example, this lesson from the Southern Agriculturalist (November, 1828) on the best way of destroying blackbirds:

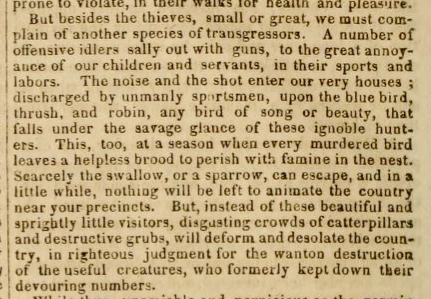

The birds which infest rice, corn, and other grain fields can be easily taken in flocks, by a spring net...[I]f this trap were used in November, December, and January, when the flocks are increased considerably, and the wild-grain food scarce, the breed of black birds etc might be considerably diminished in a few years. They are, in the planting season as annoying as certain unconstitutional measures [the tariff] are to the planting and commercial interests. The bird-minder is desired, in the spring season, to shoot principally the hen bird, this...interrupts propagation, and the gentlemen are induced to go sparking elsewhere, perhaps to your next neighbors field, where there may be better security and a greater redundancy of sweet-hearts.Nevetheless, that some farmers in the South were also supportive of some form of bird protection can be gleaned from a piece originally run in the Richmond Enquirer and reprinted in the Agricultural Intelligencer and Mechanic Register (June 9, 1820).

In some parts of the country the young Indian corn has been totally destroyed by innumerable worms of different descriptions; such as cut-worm, wire-worm, grub-worm, etc. ...Until the "Butterfly-hunters," or "Horned Cock Society" shall devise a certain cure, take the following palliative ("in mitigation of damages.") Nurse your crows and blackbirds, and all birds that devour earth worms or their larvae; of which description, the crow stands foremost, and the crow-blackbird next. That they injure corn by pulling it up, is a vulgar error.... The writer hereof has been a planter five and twenty years, and never lost an ear of corn thereby. It is true that they sometimes destroy a roasting ear by opening the shuck, but, for one thus injured by crows, hundreds are opened by woodpeckers, who do not eat earth-worms, but are useful allies to fruit and timber trees. Planters (they of the Belting system, more especially) who have dead trees in their fields for woodpeckers to build in, are incorrigible slovens, on whom even advice (cheap as it is) is thrown away. The fact is, the crow, like the dog, eats bread when he can't find meat.

This was later attributed to John Randolph of Roanoke when reprinted in the Farmer's Register in 1834 and there is no reason to doubt this (it certainly matches his lively and digressive style of rhetoric). Note a couple points of interest. First, he considered birds a "palliative" but not a "certain cure." The certain cure would have to be developed by "Butterfly-hunters" (scientific entomology was still in its infancy) or "Horned Cock Society" (natural philosophers, whom Randolph did not seem to hold in great esteem). Second, while the often persecuted crow and crow-blackbird (grackle) were portrayed as helpers, Randolph drew attention to the woodpecker as a potentially destructive force, which nevertheless could be influenced into usefulness if managed wisely (e.g., don't let them fill up on insects from dead trees if you want them to protect your orchards and timber).