Papers delivered by James Worth of the Agricultural Society of Buck County appeared in the American Farmer in 1821 (September 7. Vol 3, 24. p 190) and 1823 (March 7. Vol. 4, 50, p. 394). Worth, while primarily a livestock expert, devoted a year to studying the life cycle of the hessian fly and his findings were of urgent agricultural interest.

The section related to useful birds in the first paper is brief but is worth relating for the glimpse of the context within which Worth expresses them.

The insect tribe, though mean, is perhaps the most mischievous of all the animal creation, and when we consider its prolific nature, how careful ought we to be, to protect that link, which seems intended to keep it within its proper bounds; I allude to birds; I have already recommended them to the notice of the society, and I earnestly beg, that they may not be any longer neglected..

Note: Worth's previous "recommendations" in relation to birds are apparently not extant.

The second extract is from a paper that went beyond the hessian fly to discuss other insect threats to agriculture. Here Worth had the opportunity to more fully express his thoughts concerning the role of birds in controlling these threats.

If a fellow creature takes from us a single bushel of grain, we pursue him to the utmost rigor of the law, and yet, oh! shameful to relate, we suffer this lower grade of animals to rob us of a great portion of our store. This thing has come upon us in consequence of our wanton destruction of the feathered tribe, which is that link in creation that seems intended to keep the insect race within proper bounds, and we are left to do a work which the birds would have done for us; or rather, we are now suffering an evil that would never have happened to us. Then let us at once reform, by reversing our course of action.--The insect tribe has got the ascendancy by man's misconduct, and it devolves upon the present generation to restore the equilibrium. The increase of birds will greatly assist in the work, and I earnestly intreat that some immediate measures may be taken for their preservation.Worth began with the familiar story of "man's misconduct" and called for reform. The proposed action:

I do think that if every member of the society would absolutely prohibit gunning on his lands, it would have a good effect in discouraging a practice that, to say the least of it, is disgraceful to our nature. I rejoice to learn that in some parts of our country, the landholders have associated for that express purpose, and I understand that an association of that kind exists in Montgomery County, not far from the city of Philadelphia, where the inhabitants were almost as much annoyed by gunners as by insects: much good has been produced. Now I trust that our society will not be behind hand in this praise worthy business; and as it will not be entered upon through ill-nature, or with a view to lessen the enjoyments of any one, but as indispensably necessary for the preservation of our crops, in which the whole community are deeply interested, surely no man will be found so lost to a sense of duty and the dignity of his nature, as to oppose such salutary measures.Worth was proposing what is generally thought to be an early 20th century invention--the bird sanctuary. Moreover, he proposed including some controversial birds under his banner of protection:

Do we not remember how the blackbirds formerly followed the plough in search of grubs? Alas! that faithful bird has almost disappeared. The woodpecker and other kinds, so diligent in guarding our fruit trees, are now scarcely to be seen; the little wren, so industrious about our houses and gardens, deserves our particular care; even the despised hawk, I have observed it to be eminently useful in destroying field mice; indeed, almost every species claim our regard.

It wouldn't be until the mid-20th century that the benefits of hawks would be generally accepted.

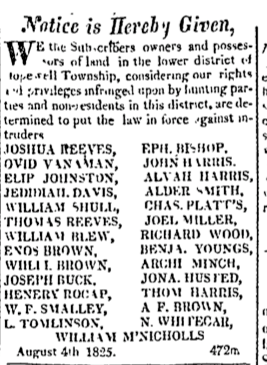

Note that restrictions on hunting were in fact more about trespassing than bird protection during this era. While I have been unable to document Worth's claim about Montgomery County, I was able to find a notice from Hopewell Township, NJ.

It ran in the Washington Whig, October 22, 1825. See the John S. Skinner complaint about ignoble hunters in an earlier post.Note that restrictions on hunting were in fact more about trespassing than bird protection during this era. While I have been unable to document Worth's claim about Montgomery County, I was able to find a notice from Hopewell Township, NJ.

In September 1822, a small item made the newspaper rounds, titled "Bird Law."

A Pennsylvania Agricultural Society have recommended to their fellow citizens to prohibit the practice of shooting birds, inasmuch as it is believed that the alarming increase of insects in that State is principally owing to the destruction of birds.While the link is not explicit it is fair to assume that this was referring to James Worth and the Agricultural Society of Buck County (he had originally delivered the second paper described above in 1822).

John Hare Powel, in a letter to the Pennsylvania Agricultural Society (published in the Society's Memoirs of 1824 and reprinted in farm papers), praised James Worth's work on the Hessian fly, and provided yet one more rendition of the idle shooter story:

Instead of being regaled by the whistling robin, and chirping blue-bird, busily employed in guarding us from that, which no human foresight or labour is enabled to avert, our ears are assailed, our persons are endangered, our fences are broken, our crops are trodden down, our cattle are lacerated, and our flocks are disturbed, by the idle shooter, regardless alike of the expensive attempts of the experimental farmer, or of the stores of the labouring husbandman; whilst all the energies of his frame, and the aim of his skill, are directed towards the murder of a few little birds, worthless when obtained. The injuries, which are immediately committed by himself and his dogs, are small, compared with the multiplied effects of the myriad of insects, which would be destroyed by the animals whereof they are the natural prey.Powel (the adopted son of Samuel Powel, the first president of the Philadelpha Society for the Promotion of Agriculture) was the author of Hints for American Farmers and a regular farm paper correspondent.

No comments:

Post a Comment